Editor's take: Black holes fascinate me. Nobody knows what goes on inside the cosmic maw. Math and physics break down as we get closer to the singularity, so we can only use our imagination to wonder what it's like on the inside, but that's okay. Theoretical cosmologist and physicist Professor Janna Levin once said, "Black holes are the ideal fantasy scape on which to play out thought experiments that target the core truths about the cosmos."

On Monday, NASA released a video showing what a camera would theoretically capture if it spiraled into a black hole (below). The clip is reminiscent of those Winamp music visualizations in the 90s (and today). It's a trippy trip into the weird math and physics of a black hole.

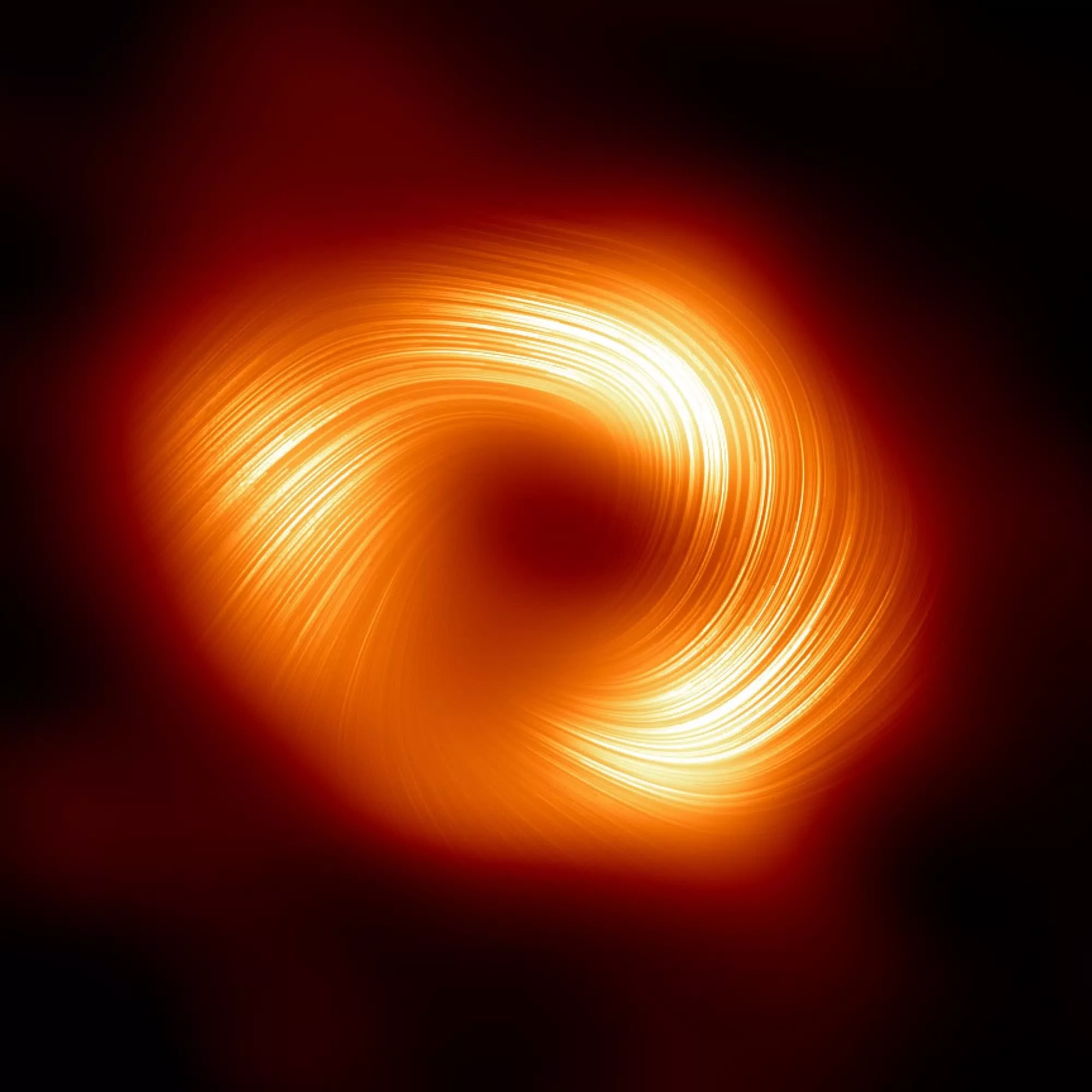

The video starts with a not-so-distant approach to the black hole, where we can see the cosmic entity in its entirety and the universe beyond. Super-heated gases form the wide outer ring called the accretion disk. The thin inner one is the photon ring. Even this thin ring has layers comprised of "distorted images of the gas disk layered between the background sky." These layers continue as photons orbit the event horizon one or more times before reaching the camera.

In the video, you can see the entire background universe smashed between layers. However, as the camera crosses the event horizon, the "sky" shifts and appears to shrink as the camera moves progressively faster.

As the camera moves from space to the accretion disk, then to the photon ring, event horizon, and finally the singularity, it accelerates faster and faster until it has to be slowed down to see what's happening. The camera acceleration becomes exponential as it moves through the accretion disk toward the event horizon in a rapidly decaying orbit. After crossing the point of no return, it only takes microseconds before the hole destroys the camera in a process physicists call spaghettification.

Spaghettification is when the part of an object closer to a black hole experiences exponentially increasing gravitational force faster than the part that is further away. It essentially stretches and crushes objects into long, thin, spaghetti-like structures, hence the highly technical name.

NASA produced the simulation using the Discover supercomputer at the Goddard Space Flight Center. It only took five days to render the simulation using just 0.3 percent of Discover's processing power. For perspective, rendering it on a typical laptop would have taken over a decade. Be sure to watch the video to the end, as NASA explains everything better than I can.